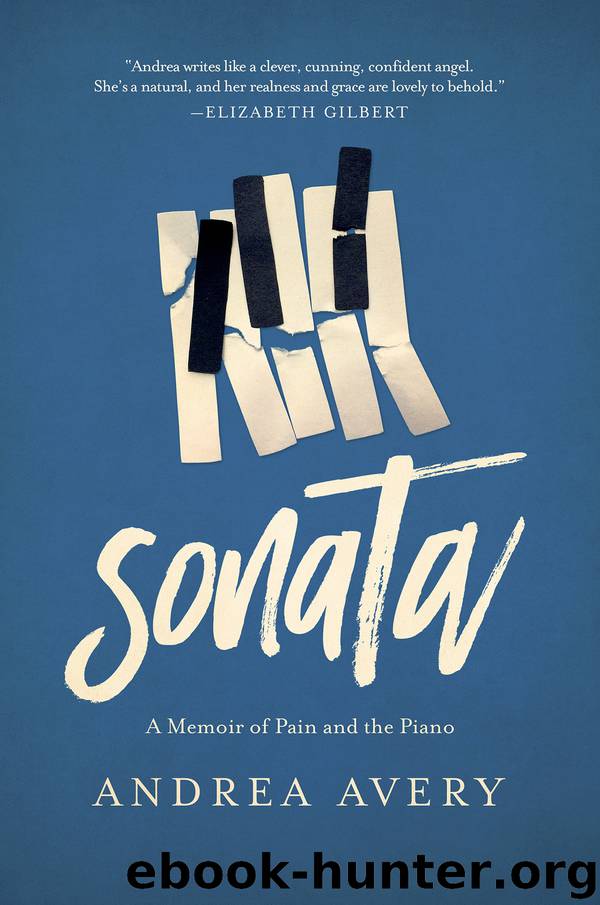

Sonata by Andrea Avery

Author:Andrea Avery

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Pegasus Books

Chapter 9

I had tried to prepare for this expulsion: in the spring of my freshman year of college, I got my first tattoo. Tattoos are like children in so many families: The first one’s a big deal, so carefully planned. The rest just sort of happen.

For two weeks before I got the tattoo, I drew it on carefully with a ballpoint pen to make sure I liked it: a black, inch-high treble clef on the inside of my left ankle. It wasn’t the most original tattoo; I was one of three freshmen in the music school to get a piece of musical notation tattooed on my body that semester.

But like everyone who has a tattoo, I believed mine was deeper, more meaningful: my tattoo was going to remind me that I was a musician, indelibly, even if a day came when I couldn’t play piano anymore. Of course, as a freshman in college, still outpacing my arthritis at the piano (just barely), I hadn’t actually believed there would come a day when I couldn’t play anymore, but it sounded good. Secretly, I hoped the treble clef would work like blood on a doorpost: to persuade arthritis to pass me over.

After the treble clef tattoo, there was a string of bass clefs on the opposite ankle. The next tattoo came when I learned about the Latin phrase festina lente—“hurry slowly”—and learned that it was a popular emblem in the sixteenth century, frequently represented by a crab and a butterfly. “Butterfly and crab are both bizarre, both symmetrical in shape, and between them establish an unexpected kind of harmony,” Italo Calvino wrote about this motto, and this symbol, in a speech he planned; he died before he delivered it.

Ten years into arthritis when I got the “crutterfly” tattoo on my right ankle, I had increasingly come to feel like a quick mind stuck in a slow body. I wanted to take every class, go to every reading, stay till the parties were over, meet everyone, and bike home at dawn. But my body wouldn’t allow me to do all of that.

Even as Schubert’s body failed him, even as he wrote in letters and his own original poems that he would “never be right again” and was “nearing final downfall,” he composed. Music poured out of him, even when hospitalized. A friend described him as “superhumanly industrious.”

Hurry slowly, I thought. Yes: I will hobble slowly to class but ask every question I can think of while I am there, during my recitative moments. I will solicit extra reading assignments, write the optional papers. I will limp everywhere I go, but once safe behind a desk or a piano or ensconced on a couch, on equal footing with everyone else, I will be a rocket ship of getting-stuff-done-ness, of making-people-laugh-osity, because I know the arias are coming. The sicker I got, the better my grades got.

Without knowing it, of course, I was submitting to a stereotype of disabled or chronically ill people, that of the “supercrip.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(31934)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(31925)

Fanny Burney by Claire Harman(26591)

We're Going to Need More Wine by Gabrielle Union(19030)

Plagued by Fire by Paul Hendrickson(17398)

All the Missing Girls by Megan Miranda(15921)

Cat's cradle by Kurt Vonnegut(15324)

Bombshells: Glamour Girls of a Lifetime by Sullivan Steve(14046)

For the Love of Europe by Rick Steves(13851)

Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson(13304)

4 3 2 1: A Novel by Paul Auster(12362)

The remains of the day by Kazuo Ishiguro(8965)

Adultolescence by Gabbie Hanna(8908)

Note to Self by Connor Franta(7663)

Diary of a Player by Brad Paisley(7544)

Giovanni's Room by James Baldwin(7315)

What Does This Button Do? by Bruce Dickinson(6194)

Ego Is the Enemy by Ryan Holiday(5407)

Born a Crime by Trevor Noah(5367)